The following article appeared in FPIF. Follow the link above for the original version.

The United States helped develop and gradually train the Afghan National Forces (ANF) to defeat the resurgent Taliban. The Obama administration is stepping up this effort. The United States plans to makes the ANF the basis of a strategy that will allow the gradual turnover of tasks in July 2011. However, the United States is banking too much on the ANF. A better approach would be to empower the tribes, their elders, and the local militias to reject insurgency and play a greater role in the politics of their country.

The United States has made some efforts in the past to use local militias but only in a limited fashion. Instead, since 2001 the United States has continuously increased its role in fighting Afghanistan’s counterinsurgency, while the indigenous fighting capabilities effectively withered or passed over to the Taliban. The 30,000 troop escalation reinforces that mentality and is likely to be counterproductive in the long run. The strategy relies on a false belief that the surge in Iraq worked because of more foreign troops. Rather, it worked because the conflict between Shias and Sunnis exhausted both factions.

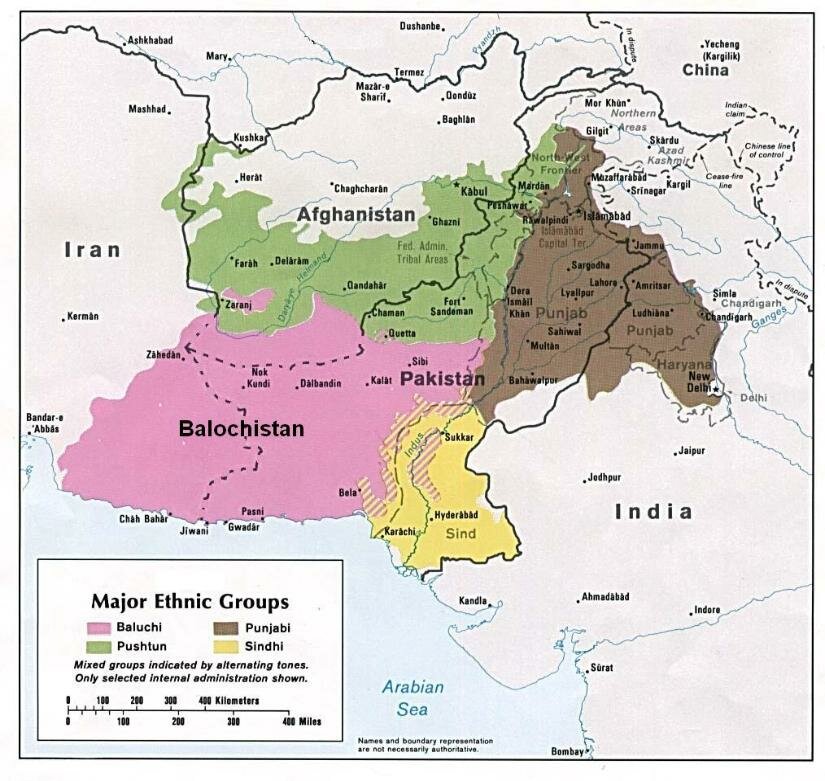

Instead, the solution lies within the Afghanis themselves and in particular the tribal system of the Pashtuns. The U.S. military must change its approach and emphasize tapping into these existing regional power structures. U.S. military officials must identify the leaders that are ready to work with the central government, reject insurgency, and do the fighting themselves instead of having foreign troops do it for them. Failure to do so will only put the ANF in the same situation that U.S. troops experienced over the last eight years — except that the Afghani army will be worse equipped and the overall governance structure will remain incoherent.

Last week, the ANF successfully defended Kabul against a brazen yet small-scale Taliban attack. But this was an anomaly. It took place in the capital away from the tribal regions. The ANF is not likely to become effective on a national level in 18 months.

First, despite last week’s successes, the ANF’s fighting capabilities have achieved a very poor record. The police and the Afghan army — the two major components of the ANF — have constantly given ground to anti-Afghan groups, which include the Taliban, other insurgent groups, and freelancing “commanders.” It has lacked the staying power, the discipline, and the courage that their opponents have. Additionally, central government agents such as the soldiers and officers of the ANF have a reputation for stealing from the population and being corrupt. The population of the rural regions often perceives the Taliban as stronger in providing security and fairer in dispensing justice.

Worse, the ANF is likely to face even greater problems. If we go by the experience of the creation of the Iraqi National Army, the ANF is likely to go through rampant desertions, defections, the possible use of the uniform to deliberately attack rival groups, and a general lack of will to fight. These problems will only become apparent when the United States presence starts to withdraw.

Furthermore, the head of the ANF training program, Maj. Gen. Richard P. Formica, has said that the ANF will not reach maximum capacity before 2013 — and that is probably an optimistic assessment. Building a modern central army is a long and expensive process.

Problems on the Ground

Afghanistan faces deep levels of corruption and fragmentation of governance which doesn’t bode well for the ANF either. “Commanders” exact fees for providing security to convoys and moving goods through their territory. These commanders aren’t part of the central government. They are essentially self-serving private groups that govern their stretch of road or parcel of territory. Some are Taliban, some are associated with them, and yet others have unclear allegiances.

The orthodox view is that the surge will knock the wind out of the insurgents and create some breathing space for the ANF and its civilian counterparts. But even a more aggressive timetable for training the ANF — which the Pentagon has asked for — is unlikely to help. In short, the United States is banking too much on the ANF.

Instead, the United States — as it still has the power to determine what direction the country takes — should go the path of least resistance and emphasize a bottom-up approach. The United States should recognize that corruption and fragmentation of power in the regions is, to a certain extent, endemic to Afghanistan. The United States should embrace this situation, rather than fight it. To do so, the United States needs to identify and empower the groups that are friendly to the central government and make every effort to reconcile those that aren’t. General McChrystal, the U.S. commander of the Afghan theater, has rightly said that “you can’t kill your way to victory.”

A Different Approach

Engaging local groups made up of tribes and warlords (or commanders) means according greater autonomy to them. Over time, they would consolidate and incorporate within the greater security apparatus of the country.

These grassroots efforts need greater emphasis — through intelligence on tribal politics, Afghan government reconciliation initiatives, and U.S. military engagement and empowerment of tribes and local leaders — because Afghanistan is a decentralized country. The most important and irreducible political unit is the tribe, at least in the Pashtun lands. Implementing a central government with western apparatus of control is akin to social engineering, bypassing the native political workings of the environment.

A centralized country has certain advantages. But going too fast with centralization (and dictating to someone else how fast they should go) risks implementing structures that are too weak to survive.

Currently, government agents lack legitimacy in the eyes of the locals, therefore giving rise to repeated accusations of corruption and injustices that erodes their capacity to operate and empowers the anti-Afghan forces. This lack of legitimacy and the weakness of the central government have created anarchy that has increasingly defined the country since 2002.

In a country where the internal politics look more like relations between states — rather than the normal relations inside a country in which the state has the monopoly on violence — self-determination is all the more important. It's also conducive to a long-term cooling down of the violence through a process of balancing power and negotiating relationships at the national level.

The Virtues of Decentralization

Yet there are many observers who see tribal politics, warlords and militias as a serious threat to the central government. Seth Jones clearly states “the U.S. assistance to warlords weakened the central government” in the aftermath of 2001. He and others believe that this kind of business is the principal reason why governance in the country has been so poor and the insurgency so strong. This viewpoint has been predominant amongst western deciders and intellectuals.

In fact, it’s the other way around: The poor governance and the resulting insurgency have stemmed from attempts to rule the country from the center in the image of modern states. The U.S. assistance to warlords was always as a last resort, done in an ad hoc fashion, and there was never any follow up to get the warlords in line with the central government. Instead, there is evidence that grassroots efforts, when properly supported, have a greater chance of success.

Ann Marlowe reported from Afghanistan last year that 250 soldiers of the 82nd Airborne were able to secure the highly contested province of Khost during their tour. The troops were able to win the support of Khost’s 13 tribes but when their tour was over the Taliban were able to regain control of much of the province, despite an increased American footprint. She also mentions the demise of a warlord in Herat that nevertheless resulted in a net security loss in the province.

Marlowe concludes:

If troops don't understand Afghan culture and fail to work within the tribal system, they will only fuel the insurgency. When we get the tribes on our side, that will change. When a tribe says no, it means no. IEDs will be reported and no insurgent fighters will be allowed to operate in or across their area.

This is a lot more than what the ANF can offer. Unlike the ANF, tribes and their leaders have the authority and legitimacy to stop their members from joining the insurgents.

Warlords in Afghanistan have a bad reputation because of their poor human rights records and their tendency to fight one another ever since the 1990s. But “warlord” doesn’t necessarily mean the big warlords of old. Rather, the label applies to any local commander who can muster a militia and garner local legitimate support. The commanders who can be friendly to the central government hold the keys to stability and rejection of the insurgency because they are legitimate elements of the social fabric.

This has been demonstrated time and again in Iraq where tribal culture is also important. The Sunni insurgency in Anbar and elsewhere, while couched in a greater national struggle, started to improve when the U.S. Army and Marines engaged rather than estranged the village elders and tribal leaders.

In Afghanistan, in the northern province of Kunduz, mounting pressure from the Taliban was successfully reversed by Bakhtiar Ludin, a former mujahedeen, and his militia after gaining the support of the central government in 2009. Mr. Ludin was helped by U.S. Special Forces, the CIA, and their Afghan counterparts. They revived the old Mujahedeen in their area — one of them was running a fish restaurant. They responded to the Kunduz governor who said if nothing was done, he’d have to side with the Taliban.

In another example, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines in Helmand province turned a bad situation around this summer by adopting a population-centric rather than an insurgent-centric approach. Gen. Michael T. Flynn explains:

Many local elders quietly resented the Taliban for threatening their traditional power structure. The Taliban was empowering young fighters and mullahs to replace local elders as the primary authorities on local economic and social matters.

Based on its integrated intelligence, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines took steps to subvert the Taliban power structure and to strengthen the elders’ traditional one.

This speaks volumes for the presence of an indigenous tribal political structure that must take a central role in the greater counterinsurgency strategy and the rebuilding of the country.

The Tajik Example

Finally, there is the experience of Tajikistan recently documented in Foreign Affairs. With a minimal budget, international efforts were able to stabilize the country in the 1990s by allowing local warlords to retain more autonomy. Instead of less effective governance, warlords were able to generate more of it because they had genuine control over their area. On the national level, an essential balance of power was struck, borders were controlled and the country eventually moved on:

Rather than forcing free and fair elections, throwing out warlords, and flooding the country with foreign peacekeepers, the intervening parties opted for a more limited and realistic set of goals. They brokered deals across political factions, tolerated warlords where necessary, and kept the number of outside peacekeeping troops to a minimum. The result has been the emergence of a relatively stable balance of power inside the country, the dissuasion of former combatants from renewed hostilities, and the opportunity for state building to develop organically. The Tajik case suggests that in trying to rebuild a failed state, less may be more.

But giving a greater role to the tribes and the militias isn't a new idea. Just over a year ago, an American-backed plan experimented with the arming of a militia in Wardak province. The Obama plan itself talks about the need for U.S. troops to work with local political units and their militias. Yet it's a matter of what elements are emphasized and whether the U.S. military can change its culture.

Even the intelligence community has severe shortcomings in the knowledge department necessary to fight a successful counterinsurgency. In a scathing report, Flynn said the intelligence community was “ignorant of local economics and landowners, hazy about who the powerbrokers are and how they might be influenced...and disengaged from people in the best position to find answers.”

Adding more troops is possibly counterproductive in the long run, because it only postpones the inevitable playing out of the situation after the Americans are gone. In the end, the solution to Afghanistan will have to come from Afghans. The sooner tribes are engaged and the the sooner American and ISAF deciders stop seeing Afghanistan through their own political institutions, the less painful it will be. If this doesn’t happen, then the fledgling ANF is likely to crumble rapidly after the foreign forces are gone. And that will only extend the U.S. mission beyond what the American public, the Afghan population, and even the U.S. military itself can tolerate.